Why Dividends Matter to Investors

What are dividends?

A dividend is a sum of money paid by a company to its shareholders, usually at regular intervals such as annually. There has been a tendency for investors to neglect dividend-paying stocks, which tend to be more mature, and instead chase after the short-term gains and ‘hype’ surrounding faster-growing companies. For the patient investor seeking returns over the long term, however, dividends are a welcome stream of income able to weather both market falls and inflation, and even to grow a holding significantly over time through dividend reinvestment.

In this insight, we will investigate the ability of dividends to:

- Both instill and indicate efficient capital management in mature businesses.

Dividend policies “leave no room for vanity projects or frivolous uses of capital”.

- Provide a simple but powerful stock selection guide for total return investors.

“Dividend payers have outperformed the broad market, and non-dividend payers significantly underperformed.”

- Deliver a proportion of total return that grows considerably over the life of an investment.

“The importance of dividend investing increases over time. Over a 20 year holding period, dividends accounted for an average 57% of total returns.”

- Deliver an even greater proportion of total returns in periods of low growth.

“The importance of investing in dividends increases dramatically in low growth decades; in the 1940s and 1970s, dividends accounted for over 75% of total returns.”

- Deliver an income stream that is much more consistent than company earnings.

“Dividends are much less volatile than earnings. Since 1940 there have been 8 years of dividend cuts, versus 25 years where earnings declined.”

- Provide a hedge against inflation.

“Divided-paying companies can, over the long term, provide an inflation hedge – dividend income grows in line with (or often at a higher rate than) inflation.”

Profits are a matter of opinion; dividends are a matter of fact

Dividends are paid from real earnings and in ‘hard’ cash. They cannot be manipulated by creative accounting. A pound paid out to the investor is just that.

If a company has a long history of paying a dividend and the intention to do so in the future, it is highly likely that management will begin each new year by first deciding the dividend payout and then thinking about how best to use the rest of the free cash flow. This leaves no room for vanity projects or frivolous uses of shareholders’ capital. A focused management team that uses the cash available to them efficiently is central to creating a well run – and profitable – company that is able to grow and thrive in the future. Steady and constantly growing dividends are a good indication that these elements are in place. Dividend payments can act as a useful identifier of companies that are disciplined and efficient in their capital allocation and cash flow management.

There exists an argument, however, that companies who pay a dividend are just struggling to find new growth opportunities and uses for their cash. We think quite the opposite. In the early stages of a company’s life it is quite right that cash is used to establish the business. It is often right that the company continues to re-deploy cash into the business as it moves through its early growth phases. However, once at maturity, when competition has entered the market place and the opportunities for continuing high growth have diminished, we think it entirely sensible that the company carefully allocates cash only to those projects where it can achieve high returns, and gives the rest back to shareholders. Why would shareholders want management to plough back all the company’s cash regardless of the returns available?

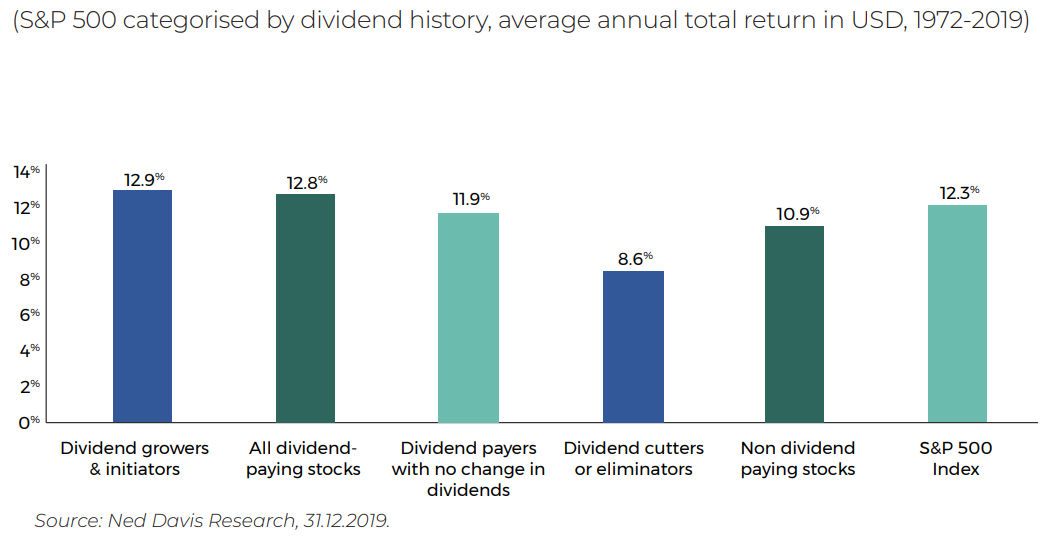

There are always exceptions to any rule, and there will always be examples of companies that have such a unique product or service that they can continue to grow for much longer than the average company. Simple mathematics, however, dictate that even these companies cannot grow forever. Indeed, looking at the historical evidence for the benefits of company management focusing on dividends, there is a strong relation between a company’s approach to dividend policy and total return performance. The evidence for this is laid out in Figure 1 below. By dividing all the companies in the S&P 500 (the leading index of the US stock market) into separate buckets depending on their approach to dividends, we can see that dividend payers have outperformed the broad market, and non-dividend payers significantly under-performed.

Figure 1 - Annualised total return of rising and falling dividend stocks

Historical perspective

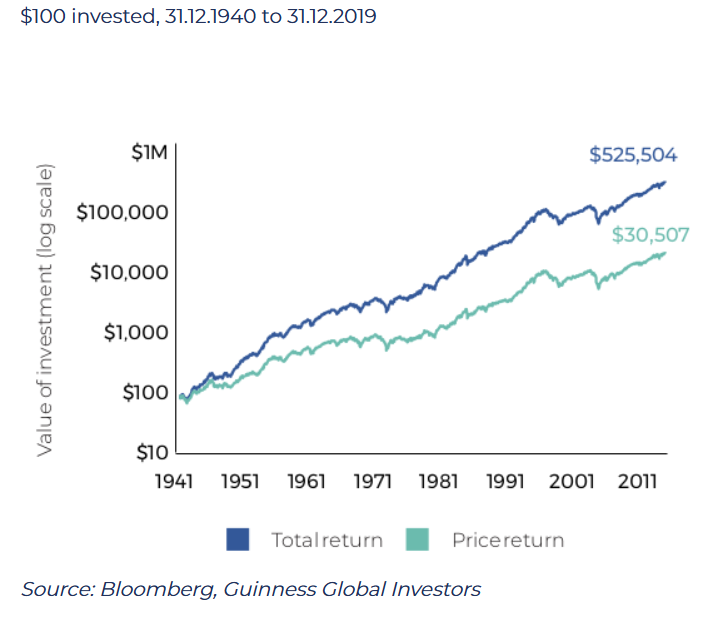

Over the long term, dividends have been the main contributors to total return in equity investments. Figure 2 illustrates this point by looking back at the S&P 500 returns since 1940. In this period, dividends and dividend reinvestments accounted for 94% of the index total return. If you had invested $100 at the end of 1940, with dividends reinvested this would have been worth approximately $525,000 at the end of 2019, versus $30,000 with dividends paid out.

This is a hugely powerful phenomenon, and one that in recent times seems to have been overlooked; investors have chased quick profits through short-term trading strategies, which come with much increased risks. The average holding period for NYSE-listed stocks between 1950 and 1970 was approximately six years. Today it is under one year, and in fact may be closer to one day when accounting for quantitative trading strategies. We believe investors should think about their investments in the long term and employ a ‘buy and hold’ strategy. This way investors can harness the power of dividends and dividend reinvestments.

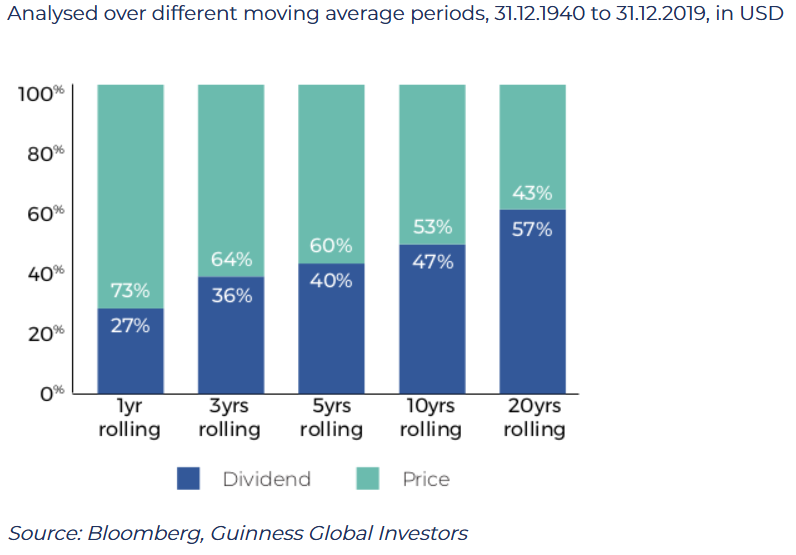

Figure 3 shows how the importance of dividends to total returns increases over time. For an average holding period of one year, dividends accounted for 27% of total returns for the S&P500 since 1940. If we increase the holding period to three years, dividends account for 36%, five years it increases to 40%, over a ten-year period it rises to 47%, and with a twenty-year holding period dividends account for some 57% of total returns.

It is important to note, too, that here we are just looking at the S&P 500 as a whole, and not focusing purely on companies that actually pay a dividend. If we did, these results would likely be even more striking.

Figure 2 - S&P 500 price and total returns, in USD

Figure 3 - Proportion of S&P 500 returns due to price and dividends

Dividend characteristics

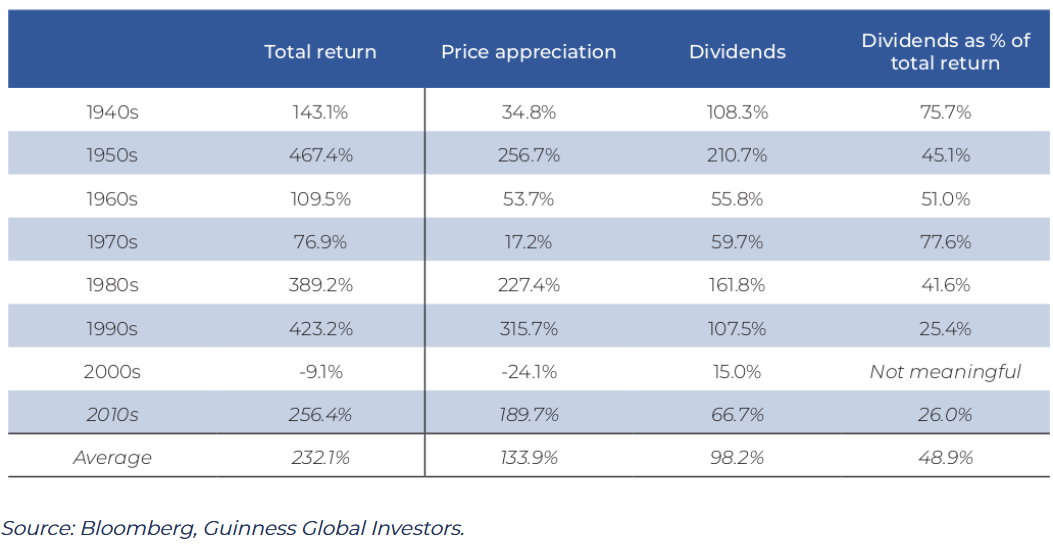

In the previous section we saw how significant dividends were to the total return of the S&P 500 over the last 80 years. If we break down this analysis into individual decades, we can see that the significance of dividends to total returns is not the same in every decade; dividends become more important in lower growth periods.

Figure 4 - S&P 500 returns for individual decades since 1940, in USD

As Figure 4 shows, the minimum contribution to total return was 25.4% (not an insignificant sum) in the 1990s, when markets rallied strongly up to the peak of the ‘technology bubble’ at the start of the 2000s. What we find more compelling, however, is that the importance of dividends to total returns increases dramatically in low growth decades, which are defined by some combination of sluggish economic growth, rising inflation, increasing oil prices, and high unemployment. In low growth periods such as the 1940s and 1970s, dividends accounted for over 75% of total returns.

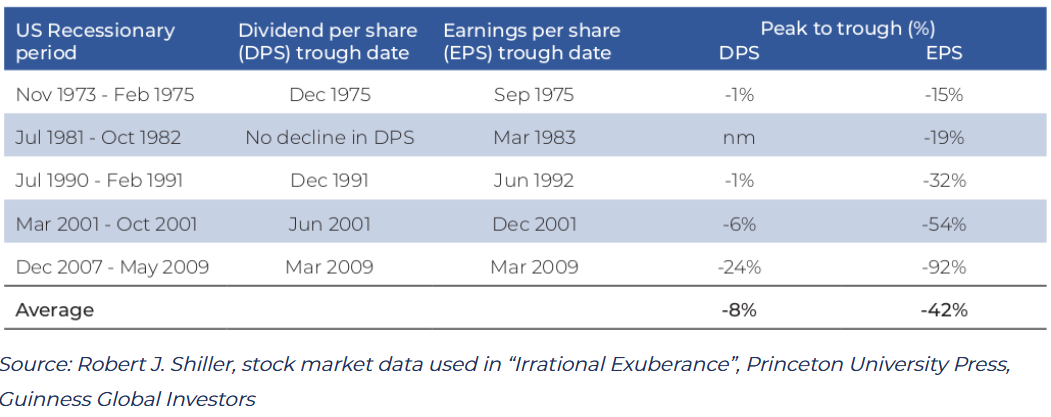

But why should dividends hold up better in difficult markets? There is no magic formula for why this might be the case – companies could stop their dividend payments to reserve cash and protect their balance sheets, and some have in the past. What we see in aggregate, however, is that companies as a group might reduce their dividend payments in particularly austere times, but rarely, if ever, collectively cut their dividend dramatically. The market sees a long history of dividend payments as establishing the credentials of a company and its management team, making significant cuts by company management more unlikely. In other words, dividends reflect the long-term earnings power of a company, and are therefore set at a level that is sustainable. If we look specifically at the last five recessionary periods in the US, as illustrated in Figure 5 below, we can see that dividends per share (DPS) for the S&P 500 dropped by 8% on average, compared to an average drop of 42% in earnings per share (EPS), i.e. dividends were cut by less than a fifth of the percentage fall in earnings over those periods (based on weighted average of total dividends and earnings).

Figure 5 - S&P 500 DPS and EPS falls in the last 5 US recessionary periods, in USD

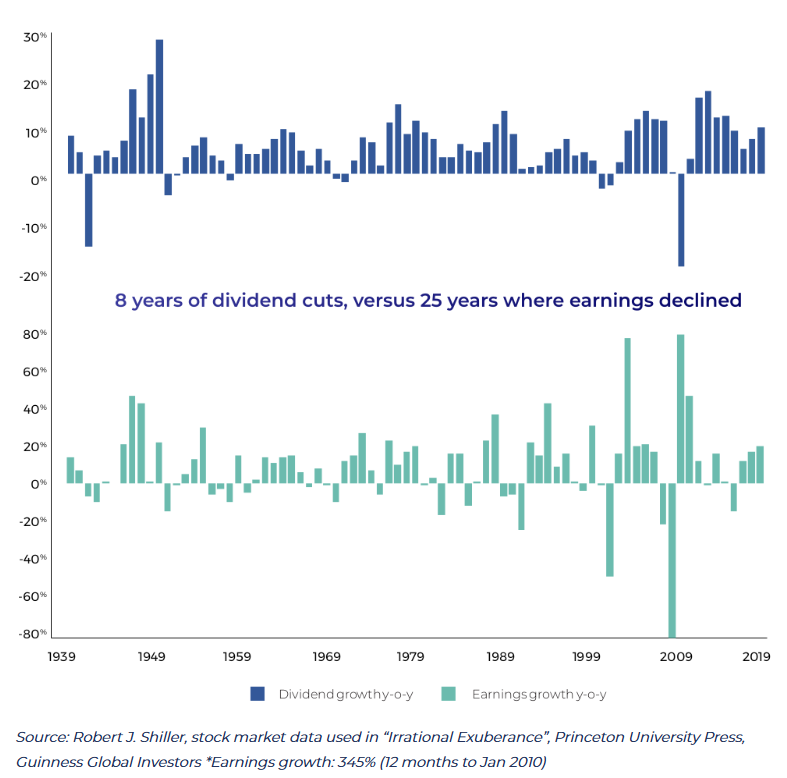

Looking at the historic year-on-year growth (or decline) in the earnings per share and dividends per share of the S&P 500, it is clear that dividends are much less volatile than earnings, as shown in Figure 6 opposite. Not only can this provide the investor with a kind of ‘cushion’ during recessionary and/or low growth periods; it can also allow long-term investors to take automatic advantage of short-term periods of low stock prices, if they re-invest their dividends throughout the business cycle (a subject we look at in detail in the next section).

Figure 6 - S&P 500 dividends per share and earnings per share year-on-year growth

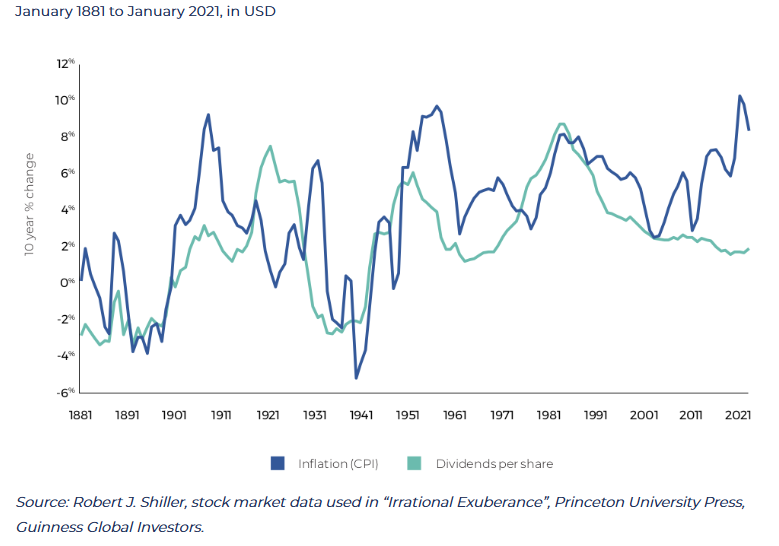

Figure 6 also illustrates the striking phenomenon that, over the long term, dividend growth is not only positive but is sustained at a reasonably high rate. Since the 1940s, over rolling ten-year periods to each year end, the average growth in the S&P 500 dividends per share is 4% per year. Over the same period, inflation grew at 2% (consumer price index (CPI) calculated by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics). Indeed, looking at the correlation of dividend growth to inflation over rolling ten-year periods, as shown in Figure 7 below, we can see a strong relationship (correlation 0.81). This shows that investing in divided-paying companies can, over the long term, provide an inflation hedge, in the sense that the income received in the form of dividends grows in line (or often at a higher rate) than inflation.

Figure 7 - Rolling 10-year growth in inflation (CPI) and S&P 500 dividends per share

The benefit of compounding

One counter-intuitive phenomenon of dividend investing is that an investor might often be pleased if the share price of the company they own actually decreases in value. Why? The idea is that investors should benefit from the fact that, if the company they own continues to pay a dividend despite the fall in its share price, the shareholder will receive a greater number of shares upon reinvestment of their income than they would have if the share price had not fallen (i.e. the investor gets to buy more shares for their account per dollar they are re-investing.) This combination of income distribution and reinvestment at more attractive valuations can be an extremely effective way to accumulate capital with relatively low risk over the long term. The key to this approach is threefold:

- Investors must be prepared to invest over the long term – so the day-to-day fluctuations in the value of their investments due to short-term market movements do not require the investor to sell down their holdings.

- The investor can identify a good quality company that can generate sustainable cash flows through a variety of market environments.

- The investee company maintains a disciplined approach to its dividend policy, and is able to continue to pay a dividend even if its share price is falling.

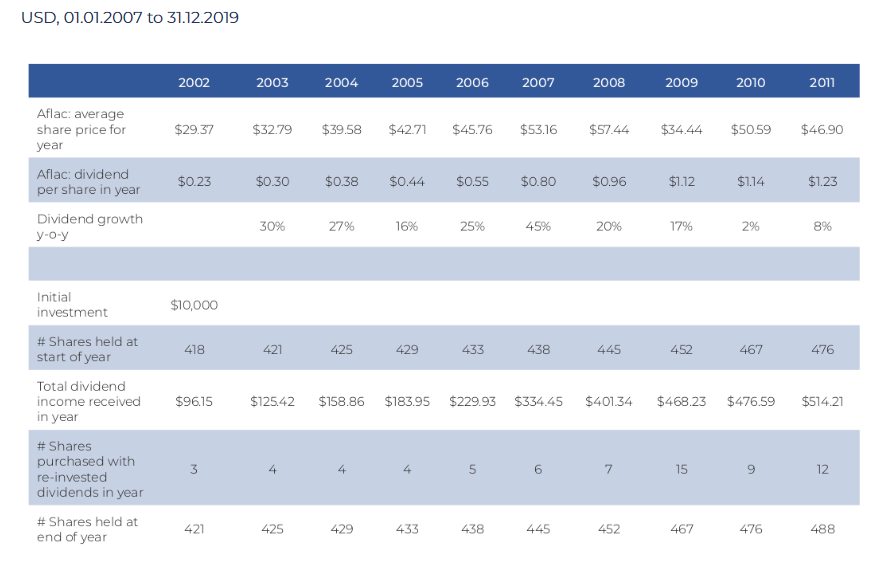

As an example, Aflac, an insurance business, has increased its dividend payment every year for the last 36 years. If we invested $10,000 on January 1st, 2007, we could calculate the number of shares we would have bought initially and also the number of shares we would subsequently have acquired by re-investing any dividends received. Figure 8 illustrates the share price performance of Aflac over the period, and Figure 9 breaks down how our shareholding would have changed with the reinvestment of dividends in each year over the period.

Figure 8 - Share price of Aflac

Figure 9 - Price history and dividend payments for Aflac

Looking at the table (figure 9), four things become apparent:

- Aflac increased its dividend per share payout in every single year;

- The number of Aflac shares held gradually increased throughout the holding period from our initial purchase of 437 shares in 2007 to 598 shares at the end of 2019 – an increase of over 30%;

- The number of shares we were able to buy with our re-invested dividends fluctuated between 7 and 8 shares in 2007/08 to the 18 shares you would have been able to buy in 2009 as the share price fell;

- During the period 01.01.2007 to 31.12.2019, the 437 shares originally held would have yielded a price return of 130%; the 18 shares bought with the dividends paid in the 2009 sell-off gave an average return of 263% from their respective pay dates until 31.12.2019.

So, although the share price fall during the 2008/9 recession was painful when we were looking at our account balance at that time, we actually benefited from being able to purchase the largest number of ‘extra’ shares with our dividend income in those years. The compounding benefit of purchasing those shares at much reduced valuations then continued into later years as the increased share balance provided a greater dollar amount of income in subsequent periods.

This is just one example of the powerful compounding effects of dividends and dividend re-investments, but there are always others out there from which the astute, long term investor can benefit.

Summary

In our opinion, when looking over the long term, dividends’ contribution to total return is compelling. We believe investors should continue to focus on companies which can maintain and grow their dividends over time. Investors should also recognise that it’s not just the blue-chip stalwarts which pay a dividend. Over the last ten years we have seen more companies in ‘non-traditional’ income sectors such as Information Technology initiate dividends. These ‘new’ dividend-paying companies can also provide the investor with the ability to capture a potentially growing income stream, which acts to further compound many of the positive effects such as inflation hedging, or the benefits of compounding over the long term, as we have illustrated in this insight.

In short, dividends still matter to investors because they offer a more systematic approach to reach financial goals over the more common ‘buy low, sell high’ strategy, allowing the more patient investor either to maximise their long-term gains through dividend reinvestment or enjoy an extra source of income, according to preference.

Explore our fund range here.

This is a marketing communication. Please refer to the prospectus, supplement, and KID/KIID for the Fund before making any final investment decisions.

Risk: The Guinness Global Equity Income Fund and WS Guinness Global Equity Income Fund are equity funds. Investors should be willing and able to assume the risks of equity investing. The value of an investment and the income from it can fall as well as rise as a result of market and currency movement; you may not get back the amount originally invested. The Funds are actively managed with the MSCI World Index used as a comparator benchmark only. The Funds invest primarily in global equities which provide a yield above the yield of the benchmark (MSCI World Index).

The insight, which can be accessed via the article links above and below, contains important information about the Funds and further details on the risk factors are included in the Funds’ documentation, available on our website (guinnessgi.com/literature)

Disclaimer: This Insight may provide information about Fund portfolios, including recent activity and performance and may contains facts relating to equity markets and our own interpretation. Any investment decision should take account of the subjectivity of the comments contained in the report. This Insight is provided for information only and all the information contained in it is believed to be reliable but may be inaccurate or incomplete; any opinions stated are honestly held at the time of writing but are not guaranteed. The contents of this Insight should not therefore be relied upon. It should not be taken as a recommendation to make an investment in the Funds or to buy or sell individual securities, nor does it constitute an offer for sale.